Where did the English language come from?

The earliest known language in England was Goidelic (q-Celtic)which spread into England from the continent. A second form, Brythonic (p-Celtic), followed. Goidelic led to the formation of the three Gaelic languages spoken in Ireland, the Isle of Man and later Scotland. Brythonic developed into Welsh, Cornish and Breton, spoken in Brittany. The Celtic languages were the forerunner of English in these islands but, with the Roman invasion, vulgate Latin arrived and supplanted the Celtic tongue for business and military purposes in the areas of Roman influence. In writing, the Celtic runes were replaced by the Roman alphabet.

English (Old English) developed when the Romans abandoned England and a

collection of Germanic tribes including the Angles, Frisians, Saxons and Jutes moved in to colonise the country. The language

they developed was tremendously complicated with nouns having genders (as they still do in other languages today), verbs having

ten different classes and adjectives changing into different forms to match gender, singular and plural. On the plus side every

letter was sounded and a written language appeared using Roman letters to replace the runes that the tribes brought with them.

There were however certain sounds represented by runes that

were not characters in the Roman alphabet so four runes were kept in small and capital letters —

ƿ Ƿ called ‘wynn’ and pronounced as w —

þ Þ called ‘thorn’ and pronounced as in this and that —

ð Ð called ‘eth’ was used for a soft ‘th’ as in thick and

thin) — ȝ Ȝ called ‘yogh’ was used for a y or g sound

depending on the word.

In handwritten scripts the word ‘the’ þe was often written as

![]() but still pronounced as the not ye).

but still pronounced as the not ye).

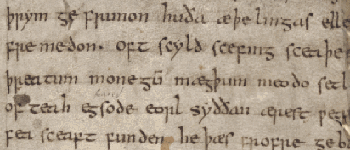

from the poem Beowulf

11th century manuscript

from the poem Beowulf

11th century manuscript

The Viking invasions could have overwhelmed English but, with the truce along

the Danelaw boundary across England, Old Norse and Old English gently merged. Today we have craft from

Old Norse, skill from Old English. The pronouns they,

them and their were a particularly useful Scandinavian addition to English.

The Norman invasion nearly destroyed English as court, parliament and the ruling classes all spoke Norman French. However by a quirk of fate, their French dialect was different from the correct Parisian French and as the years passed it became more and more rustic-sounding to French ears. Norman nobles resorted to having their sons educated in France but gradually they became proud of their English heritage and the English language. Because it had been relegated for so long to being the people’s language, English had changed. To suit everyday usage, genders had gone, grammar was simplified and vocabulary had been vastly enriched with Norman-French words. In fact possibly ony 5,000 Old English words survived the Norman period but they include so of the most fundamental and widely used even today - man, woman, live, love, eat, drink, sleep, wife, child, brother, sister, and, but, for, in, on.

When the Norman scribes took over government written documents they got rid of

þ and ð and q, g and

z were added to the alphabet. A symbol the Normans used was the Tironian shorthand for ET (from Latin)

in various forms  used to replace the word

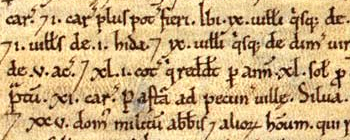

‘and’. A famous Norman book looked like this -

used to replace the word

‘and’. A famous Norman book looked like this -

Domesday Book 11th century codex

Domesday Book 11th century codex

The English language that followed on from Anglo-Norman is known as

Middle English and despite simplification there was still a wide variety of local dialect words, spellings and pronunciation.

In 1500, a few miles could take you to a place where they would have difficulty understanding you. Up to Chaucer’s

time the letter e was used and pronounced at the end of a number of words such as . Chaucer would rhymed

good, hood, stood and wood with our food

and sheep was pronounced shape.

When in 1475 William Caxton set up his printing press in London he

used an East Midland dialect for spelling which covered an area covering London and also the important seats of learning,

Oxford and Cambridge. He was born only 22 years after Chaucer ’s death but his vocabulary and spelling are much

closer to modern English.

There was also, particularly through the fifteenth and early sixteenth

centuries, a major change in pronuciation called The Great Vowel Shift. For the word life

Chaucer wrote lyf and spoke it as leaf; Shakespeare wrote

life but pronounced it lafe. Before the shift ‘house’

was pronounced ‘hoose’ and ‘blood’ rhymed with ‘food’. When Chaucer died in 1400

people still pronounced the ‘e’ on the end of words such as ‘booke’ and ‘clerke’.

100 years later the ‘e’ had become silent and in due course disappeared from the spellings as well.

In Elizabethan times many ‘er’ words were pronounced as

‘ar’ so serve would rhyme with carve. In modern English

clerk and heart are still pronounced as ‘ar’ although

the former and most other ‘er’ words have been revised in American English so that clerk

now rhymes with work.

Words which came early from French and those that were borrowed later are

often pronounced differently, for example cabbage coming early has an -idje sound and

camouflage arriving later was given an -arje sound. ‘Ch’ in

chair is differerent from ‘ch’ in chamfer though both are

from the French. So pronunciation can give us clues as to the origins of words.

Through the 1500’s thousands of completely new words were made up. In

Shakespeare’s plays he introduced leapfrog, countless,

lonely, excellent, gloomy and many other words

which are original including some local words which generally didn't take root and weren’t repeated in the later plays.

Some words came from overseas. The word bankrupt is formed from Italian “banca rotta” meaning

“broken bench” from the early days of open-air banking when your bench was broken to signify you were finished in the

profession.

Over the years, word meanings change but sometimes there are clues as to a

former life. At Christmas we eat mincemeat which is made entirely of fruit but in the past did include

minced meat. To prove used to mean to test and a ‘proving ground’

was an area where something was tested. The phrase “the exception proves the rule” makes a little more sense if

understood as “the exception tests the rule”.

In the twentieth century new words were coined but not in the personal human

field. They are most often based on technology and medicine so we have recently added words such as

psychosomatic, snowboard, quark,

emoticon, spyware.

Sources:

Bryson, Bill Mother Tongue Penguin Books 1990Bragg, Melvyn The Adventure of English BBC series