How did books first appear in England?

The earliest inhabitants carved runes onto strips of wood and the Romans brought written wooden tablets which have been discovered at Vindolanda fort on Hadrian’s Wall. However it is a big step from these to the modern book and various events moved the story forward.

Parchment was in use from about the second century BC in Greece and is made from the split sheep’s skin. The grain, or wool, side of the skin is used for leather but the inner side of the skin is converted into parchment. Particularly good quality is needed to provide a smooth surface and inferior skins were made into chamois or suede. It only stopped being used when the much cheaper material, paper, arrived coinciding in England with the invention of printing.

The earliest form of bound book was the codex. It was handwritten on vellum, a fine form of parchment, which is usually calfskin prepared by a lengthy exposure in lime, scraped and rubbed smooth. It is usually made from the entire skin, not split as is parchment and goat, lamb, and deerskin were also used. It is less regular than parchment with grain and hair marks appearing. The pages were square and had wooden covers which helped to keep the pages from curling and sometimes metal clasps were added. The title of the codex was usually written at the end of the text with perhaps the scribes name and the date. This little appendix was termed a colophon.

The Chinese had invented paper hand-made from clothing fibres, cotton and linen, around the second century (and block printing using clay blocks soon after). It took until the twelfth century for the Moors to set up a papermaking mill in Spain. Medieval paper was made from linen rags and it was not until around the mid-nineteenth century before wood pulp was utilised. Incidentally modern paper is inherently less stable than cotton or linen fibre paper.

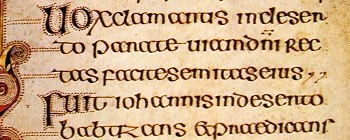

Book scripts began with the first distinct script known as Capitalis Quadrata or Square Capitals around the 1st century BC. This was followed by Capitalis Rustica up to the fifth century; both these scripts only used capital letters. Then came Roman Uncials and Half-Uncials which were used for books up to the eighth century. (Insular) Half-Uncials were used in the Lindisfarne Gospels.

After the Norman Conquest, Caroline Minuscule hand was used for books (a hand developed by an English abbot, Alcuin of York, in the monastery at Tours and used in Charlemagne's empire between approximately 800 and 1200) and further developed, from around 1150, into various forms of what is called Blackletter or Gothic Script —

Until into the 12th century, most written documents were produced in monasteries by monastic scribes and held in monastic libraries. However by the end of the 13th century, secular scribes were being employed in towns and villages to record official transactions. Manorial bailiffs nedeed written records for management of the estate and clerks were employed to draw up accounts, send letters and keep records. The universities had been set up by this time and the increased need for books for study purposes led to a new profession appearing. That of stationer. He would bind the books, which involved stitching the sheets of parchment on to leather strips or cords set across the spine. The cords were then threaded onto the wooden board covers and fixed down. The boards were usually covered with leather which in time was stamped with decoration.

One of the most popular books of the very religious Middle Ages was the personal prayerbook known as the Book of Hours. It included prayers, hymns and psalms together with other bible passages. They were small highly decorated books often commissioned as wedding gifts for the bride.

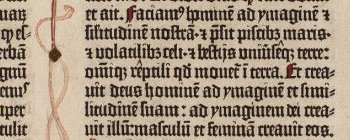

Printing first appeared when Johannes Gutenberg brought his printed bible to the Frankfurt Fair in 1455. They were quarto-sized with two columns of 42 lines each per page and the typeface was designed to give the look of a manuscript as the printers wanted their productions to have the hand-written look and it was in Latin. Curiously, most of the 200 or so copies of Gutenberg’s bible were printed on paper but about a quarter were printed on vellum.

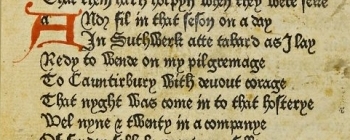

The name for the earliest printed sheets and books, up to around 1500, was incunabula roughly meaning ‘the early stages’. A noted incunabula was Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales edited and produced by William Caxton. The 1476 edition is especially interesting as it was probably the first major work to be produced in England, printed on paper and in English! —

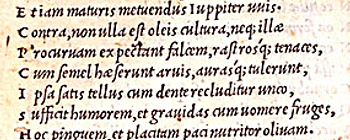

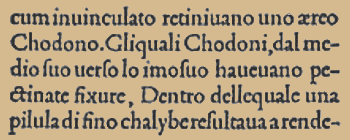

However developments were happening abroad and an important new typeface was introduced by Teobaldo Mannuci (Aldus Manutius) in Venice, Italy using letter designs created by a punch-cutter and former goldsmith from Bologna named Francesco Griffo also called Francesco da Bologna. Griffo was said to be working from the handwriting of the Italian poet Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca).

In 1500 Mannuci’s Aldine Press produced a volume of the letters of St. Catherine (above) introducing the new typeface which being easier to read when printed small was ideal for more compact, less expensive, books. It was called Venetian but later became dedicated to Italy and known as italic. The typeface was first used for his Virgil:Works in 1501 which was also a first in being produced in 8° (octavo) size - that is, eight leaves each about 9˝" x 6Ľ" being folded from a standard sheet of paper 25" x 19" —

Bembo typeface was an earlier more upright typeface cut by Francesco Griffo for Manucci to publish ‘De Aetna’ by Cardinal Pietro Bembo in 1495. It was preferred for printing classics and literary texts as against the more formal Gothic Script. It also keeps a handwritten-look with a delicate curve from the serifs into the stem of each letter. The lowercase c has a subtle forward slant and h, m, and n have a slight returned curve on their final stem. His types also differed from earlier Venetian forms is the way in which the ascenders of the lowercase letters stand taller than the capitals.

Garamond typeface is a classic design produced by the French 16th century typecutter, Claude Garamond, and it became a standard among book designers and printers for four centuries. This type is based on Roman inscriptional letterforms for the capital letters and Caroline minuscules for the lowercase letters —

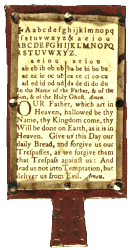

The hornbook was used by students as an early reader from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. A thin wooden board had a printed paper stuck to it the a thin transparent layer of horn placed on top to keep the paper clean and a thin brass frame fixed to hold the parts together. The words usually included the alphabet, perhaps numbers and the Lord’s Prayer in English. It was expensive to produce as the horn required a lot of work to manufacture the thin sheets needed.

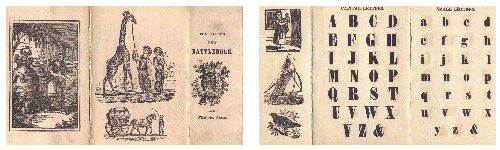

Like the hornbook, a battledore was also an early kind of reading book for young children. Named after the bat used with a shuttlecock because of their shape, they were made of thin cardboard and replaced hornbooks when the price of paper became cheap. The card was usually cut into the shape of a rectangle and then folded in thirds. However, some early battledores were actually shaped like hornbooks. Battledores were introduced in England in the late 1700’s. The content of a battledore was similar to that of a hornbook including the alphabet in both capital and small letters, pairs of letters, and lists of short words. However they normally also had a short story or fable and illustrations.

The London New Battledore 1825

In the seventeenth century hawkers sold little booklets which became known as chapbooks. They were octavo size so that a single printed sheet could be folded and cut to produce a sixteen page booklet. The subjects included almanacs, ballads, historical romances and short novels. Samual Pepys had a collection which is now held at Magdalene College, Cambridge and the Bodleian Library in Oxford also has a collection. In the 1800’s nursery stories and rhymes for children began to appear.

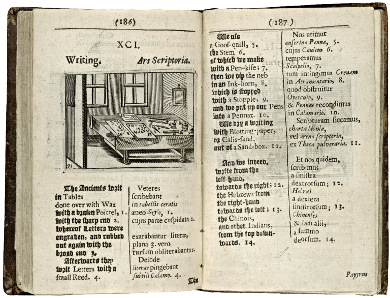

In 1658 probably the first pictorial encyclopædia for children was published in Germany. It was to be used to teach children Latin in school and was written by a Czech minister and educator, Jan Amos Komenský (1592-1670), who had visited England in 1641/2 when the engraving on the frontispiece was done by T. Cross.

It was called Orbis sensualium pictus ‘The Visible World in Pictures’ and was written in Latin and German with over 100 woodcut illustrations. The book was translated into English by Charles Hoole, M.A. with new copperplate engravings and appeared in in 1659.

This edition was published by Samuel Mearne, his Majesties bookseller, at the Kings Arms at Charing-Cross, London in 1672. It was subsequently translated into many languages and ran to over 200 editions.

These particular pages explain writing and printing. He uses an interesting device whereby he attaches numbers to parts of the picture and refers to these in the text.

The book ends with these words:

Thus thou hast seen in short all things that can be shewed and hath learned the chief words of the English and Latine Tongue. Go on now and read other good books diligently, and thou shalt become learned, wise, and Godly. Remember these things; fear God, and call upon him that he may bestow upon thee the Spirit of Wisdom. Farewell!

A gallery of books over the centuries:

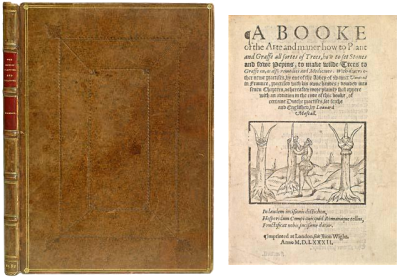

Leonard Maskell 1582

A booke of the arte and maner how to plant and graffe all sortes of trees,

how to set stones and sowe pepins, to make wilde trees to graffe on,

as also remedies and medicines ...

William Lowndes 1695

‘A Report Containing an Essay for the Amendment of the Silver Coins’ by a treasury

official, William Lowndes. A presentation copy bound in black morocco leather.

The Royal Kalendar 1793

Including a complete and current list of the 17th Parliament of

Great Britain summoned to meet for their first session in November 1790.

Cloth replaced leather for binding books in order to reduce costs and was used in a series called Diamond Classics published by Pickering in 1822.

Sources:

Richard Miller A Brief History of the Alphabet from the CBBAG Newsletter Summer 1996British Library Treasures in Full, Gutenberg Bible http://www.bl.uk/treasures/gutenberg/homepage.html

Bernard J Shapiro Rare Books, 32 St George Street, London W1S 2EA http://www.shapero.com/index.php